Teen Council Blog

July 11, 2024

Simply Put, Music Can Heal People

Written By Guru Aroul

âMusic can heal the wounds that medicine cannot touch.â â Debasish Mrihda

Music has been a fundamental part of our existence for thousands of years. It has emerged as an instrument of order in a disorderly world, transforming dissonance into harmony and chaos into rhythm. Our understanding and mastery of music have also evolved alongside our civilizations. Today, it is a refined art form shaped by millennia of theory and practice. As the art developed, our understanding of its impact on us has grown as well. Musicians utilize emotional connections to create masterpieces that move oneâs heart. It’s no wonder, then, that people consider music to be therapeutic. This realization prompts an important question: Can music be used as a therapeutic intervention? It was only since the 1800s that music therapy has become an acceptable intervention in the medical field.

According to the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA), âmusic therapy is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program.â Doctors have acknowledged that music therapy is a great supplementary intervention and helps a lot in treating people with neurodegenerative disorders and neurodivergence. Patients with dementia, Parkinsonâs disease, schizophrenia, etc., have shown tremendous improvement after undergoing music therapy. Since there isnât a cure for these neurological disorders, music therapy is not only a viable option but also an impactful intervention.

The brain is an intricate organ crucial for the functioning of the human body since it commands all the other organ systems. It acts as the center of our imagination and conscience. This is, ironically, the least understood function of the brain. Although it is arguably the most important organ in the human body, scientists only know about 10% of the brainâs functions. Many studies have shown that listening to music benefits the brain. Each noise and sound are different, affecting the human body differently. Specific wavelengths help the brain by stimulating essential parts of it, while others do not have such an effect. The rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic aspects of music activate cognitive, motor, and speech centers in the brain. Rhythm creates order and structure in music making it pleasant to listen to. Melodies temporarily ease and sharpen our minds. Harmonies activate parts of the brain that regulate emotions. The combined effects of these three aspects of music make it therapeutic. Over a period of time, music-based therapy/interventions can have sustained effects potentially even reversing some neurological conditions.

Music-based intervention sessions can be administered both as individual and group therapies. They can be either interactive with the patients actively involved with the therapists by singing, dancing, playing instruments, etc. or just as a passive listener. The therapist creates exercises specifically tailored for the patient’s needs. Exercises include remembering rhythms or melodies for cognitive therapy, clapping to a rhythm or dancing to a tune for motor therapy, and singing for speech therapy. These exercises allow the patient to gain more control over and train many crucial parts of their brain. For some patients, results can be seen in a few sessions. For others, however, it may take longer. Music therapy is like physiotherapy for the brain — you may NOT see immediate improvements. It takes time, but significant progress can be made. For children with neurodivergence especially, using music as therapy has been shown to evolve them on the physiological level. Using music intervention from a young age can even curb symptoms of ASD and other neurodivergent conditions.

Music therapy is a relatively recent intervention technique, so more research is imperative to effectively use specific rhythms, melodies, and harmonies to stimulate the brain and trigger cognitive healing. Building these neural connections is pivotal to making patients more functional by developing their weaker cognitive areas. Therefore, therapists can use music to initiate neural processes resulting in tangible, therapeutic benefits.

I thank Dr. Sri Nippani for his mentorship and support.

April 11, 2024

Elaine Shaffer: The Woman Who Accomplished the Impossible

Written By Audrey Timoszyk

As we wrap up womenâs history month, I wanted to share the story of a woman who achieved so much during her life, who inspires me even fifty-one years after death, but whose name has been forgotten. Elaine Shaffer was one of the first female soloists to launch a successful career. She carved a place for herself in a world that was often unwilling to recognize her. Through her artistry, bravery, and hard work, Elaine Shaffer proved that the world was wrong to keep women from the stage.

Elaine Shaffer was born in Altoona, Pennsylvania. She would later become one of the greatest flutists of her time, but until she went to college, she was largely self-taught. Nevertheless, Shaffer was able to become a very fine flutist by listening to recordings, mostly those of the Philadelphia Orchestra with William Kincaid, and by experimenting with techniques on her own. When Shaffer graduated high school, she sent William Kincaid a letter asking him if she could play for him and potentially become his student. Kincaid was so impressed with her playing that he offered her a place at the Curtis Institute of Music, one of the best conservatories in the world, on the spot. Shaffer was incredibly successful at Curtis, and after graduating, she played with the Kansas City Philharmonic and became the principal flute of the Hollywood Bowl Symphony and later the Houston Symphony. However, after a few years of playing in orchestras, Shaffer began to feel restless. Orchestral music didnât pose the challenges that Shaffer was looking for, and she was tired of counting rests. Because of this, Shaffer decided to launch a career as a soloist. Shafferâs career quickly took off after a debut performance in London. Her playing was loved by thousands, and her artistry took her to Paris, New York, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Belgrade, Lucerne, Gstaad, Venice, Madrid, Berlin, Frankfurt, Vienna, and Leningrad. Shaffer played with all of the worldâs best orchestras and she achieved widespread fame. Her most ambitious project, a memorized performance of all of Bachâs flute sonatas, was so difficult it had never been done before. Nevertheless, Elaine Shaffer played all six of them in Londonâs Queen Elizabeth Hall and became the first person to ever accomplish that monumental feat. Elaine Shaffer died of lung cancer in 1973. She was forty-seven.

Throughout her career, Elaine Shaffer faced challenges. However, the most difficult obstacle and the hardest one to overcome was the issue of her gender. Shaffer lived during a time when women just werenât allowed in orchestras. If you went to see the symphony, a sea of men in suits would greet you from the stage. If you were lucky, maybe you would see a female harp player. This was an era where female musicians, especially soloists and most especially conductors, were considered very unusual and would often draw a lot of controversy. Needless to say, even though William Kincaid, widely considered the best American flutist of the time, declared that Shaffer was better than he was and added that âCurtis should instal a monument of [her] because they had never achieved anything equal to what [she] had done,â it was extremely difficult for Shaffer to get an orchestral job. When the Baltimore Symphony was hiring flutists, they included âONLY MEN WANTEDâ in the job description. When Shaffer applied for the principal flute position of the Pittsburgh Symphony under Fritz Reiner, she had to wait for âalmost three hours and had to talk with [Reiner] for a while before he would even let [her] play.â Reiner decided not to hire her even after telling Shaffer, ââYou are the best I have heard, but too bad you are a woman.ââ After rejections from many orchestras who loved her playing but still would not take her, Shaffer wrote that she felt âso alone in [her] disappointmentâ that she âjust wanted to go somewhere and cry [her] eyes out.â Shaffer eventually earned positions with many different orchestras, but her career as a soloist was also difficult. While Shaffer was welcomed as a soloist most of the time, she was occasionally disrespected by members of the orchestras she played with. Shaffer was constantly concerned about how conservative audiences would receive her performances, and reviews of her concerts often spoke about what she was wearing as much as how she sounded. Even so, Shaffer never let those obstacles stop her from achieving her goals, and she actively pushed back on discrimination she faced because of her gender.

In todayâs orchestras, there are all kinds of programs that encourage diversity within ensembles. Auditions are usually screened to prevent bias. Many orchestras work to program female conductors and composers. Maternity leaves exist for people who work in orchestras and nursing rooms are sometimes available in concert halls. If you proposed any of these things to the people who officiated the orchestral auditions of the 1940s, they would have stared at you like you had three heads. I am so thankful for the opportunities that women have now, and we only have them because people like Elaine Shaffer fought to show the world that they were wrong to keep women from roles that were held exclusively by men. I admire Elaine Shaffer so much. She had the courage to push past rejection until people forgot why they rejected her in the first place. Her artistry spoke louder than any words.

December 13, 2023

The Evolution of the Orchestra: A Journey Through Time and Sound

Written By Akshara Saireddy

The orchestra, as a complex ensemble of diverse instruments, has undergone a fascinating evolution throughout history. This paper explores the roots of orchestral music, tracing its development from ancient civilizations to the sophisticated ensembles of the present day. Examining the evolution of orchestras allows us to understand the societal, cultural, and technological influences that have shaped this musical institution over centuries.

Ancient Origins:

The origins of orchestral music can be traced back to ancient civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece. While these early ensembles were not orchestras in the modern sense, they laid the groundwork for the collaborative performance of instruments in organized groups. The Greeks, for instance, had aulos players and lyre players performing together during religious ceremonies and theatrical events.

Medieval and Renaissance Periods:

The medieval and Renaissance periods saw the emergence of proto-orchestral ensembles, such as the alta capella groups featuring shawms and sackbuts. These ensembles provided entertainment at royal courts and during festive occasions, gradually incorporating a wider range of instruments.

Baroque Era:

The Baroque era witnessed a significant expansion of the orchestra. Composers like Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel contributed to the development of orchestral music by introducing the concerto grosso and the orchestral suite. The establishment of the standardized orchestra began to take shape with string, wind, and percussion instruments.

Classical Period:

The Classical era, marked by the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, and Ludwig van Beethoven, brought further refinement to orchestral composition and instrumentation. The establishment of the symphony orchestra with a standardized instrumentation and the rise of the conductor as a central figure marked this period.

Romantic Era:

The 19th century witnessed a surge in emotional expression and experimentation within orchestral music. Composers like Hector Berlioz and Richard Wagner expanded the size of the orchestra and introduced new instruments, such as the saxophone and the Wagner tuba. Programmatic content and thematic development became prominent features during this era.

20th Century and Beyond:

The 20th century witnessed unprecedented experimentation and diversification within orchestral music. Composers like Igor Stravinsky, Bela Bartok, and Dmitri Shostakovich challenged traditional tonality, and new playing techniques and electronic instruments were incorporated. Film scores, influenced by orchestral arrangements, gained prominence, contributing to the popularization of orchestral music.

Contemporary Orchestras:

Today, orchestras continue to evolve, embracing a wide range of styles and genres. Contemporary composers explore innovative sounds, and orchestras collaborate with artists from diverse musical backgrounds. Technology has also played a significant role, with digital advancements influencing composition, performance, and recording.

December 7, 2023

The Timeless Significance of Classical Music

Written By Akshara Saireddy

Classical music stands as a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and expression. Its rich history, spanning centuries, has left an indelible mark on the cultural tapestry of societies worldwide. From the intricate compositions of Mozart to the profound symphonies of Beethoven, classical music has withstood the test of time, captivating generations and transcending cultural boundaries. This essay explores the importance of classical music, delving into its cultural, emotional, and cognitive significance.

Cultural Significance:

Classical music serves as a repository of cultural heritage, preserving the artistic achievements of various eras. Composers like Bach, Mozart, and Chopin have contributed masterpieces that reflect the aesthetics and values of their respective times. The symphonies, concertos, and operas composed during the Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and Contemporary periods offer a glimpse into the evolution of human thought and emotion.

Furthermore, classical music is often intertwined with historical events and societal changes. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, for instance, has become synonymous with the ideals of freedom and brotherhood, serving as the European Anthem. By immersing ourselves in classical compositions, we connect with the cultural roots of our past, fostering a sense of continuity and shared human experience.

Emotional Impact:

One of the distinctive features of classical music is its ability to evoke a wide range of emotions. Composers harness the power of melody, harmony, and rhythm to create sonic landscapes that resonate with listeners on a profound level. Whether it’s the exuberance of Vivaldi’s “Spring” or the melancholy of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake,” classical music provides an emotional outlet, allowing individuals to experience and process a spectrum of feelings.

Moreover, classical music has therapeutic qualities, with studies suggesting its potential to reduce stress, anxiety, and improve mental well-being. The intricate patterns and soothing melodies inherent in classical compositions have a calming effect, offering solace in a fast-paced, modern world.

Cognitive Benefits:

Engaging with classical music also yields cognitive benefits. Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive impact of listening to classical music on cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and problem-solving skills. The intricate structures and complex arrangements challenge the brain, promoting neural connections and enhancing cognitive abilities.

The “Mozart effect,” a phenomenon suggesting that listening to Mozart’s music can temporarily boost spatial-temporal reasoning skills, has gained attention in educational settings. While the long-term effects remain debated, it underscores the potential of classical music to influence cognitive processes positively.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, classical music holds a timeless and multifaceted significance in our lives. Its cultural richness, emotional depth, and cognitive benefits contribute to its enduring appeal. By immersing ourselves in the masterpieces of classical composers, we not only connect with the cultural heritage of humanity but also experience the profound emotional and cognitive impact that this art form has to offer. In a world filled with constant change, classical music stands as a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and the capacity of art to elevate the human experience.

March 29, 2023

The Rite of Spring: A Path-Breaking Work

Written By Aditya Shivaswamy

The music opens with an odd, haunting melody, calling for nature to awaken. You look to see from which instrument that eerie, otherworldly, unidentifiable, high-register tune comes, until you realize that it’s the … bassoon? According to popular legend, the composer Camille Saint-SaĂ«ns, incensed by the unorthodox use of the instrument, usually played in the deep bass range, stormed out of the theater when he heard it, shouting, “If that’s a bassoon, then I’m a baboon!”

Sacre du printemps or The Rite of Spring is a ballet and orchestral work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, which premiered in Paris in 1913 to a divisive reception. The ballet, which is split into two parts, “The Adoration of the Earth” and “The Sacrifice,” tells the story of a group of ancient Slavs who celebrate the arrival of spring by performing a ritual sacrifice. The music and choreography of The Rite of Spring were unconventional and groundbreaking for their time, featuring experimental uses of tonality and dissonance and disconcerting pieces of primitive, pagan imagery.

When one thinks about ballet, he or she would likely envision a beautiful, graceful dancer, moving across a stage in flowing lines with intricate choreography. The Rite of Spring is different — much, much different. Dancers move in angular, jerky movements, stamping and running around in dizzying circles rather than performing dazzling pirouettes or soaring grande jetĂ©s. The choreography, created by Vaslav Nijinsky, was derived from the traditional ancient Slavic dances of Russia that Stravinsky studied for inspiration. But as the ballet develops, the power of the dance enchants, precisely what Stravinsky sought. He wrote the ballet to showcase the importance of nature and ritual.

Stravinsky’s score for The Rite of Spring is just as unconventional as the ballet’s choreography. The music is harsh and dissonant, with pounding rhythms and strange, angular melodies that are meant to evoke the primitive, pagan world of the Slavs. The orchestration is similarly unusual, with unconventional instruments like the bassoon and contrabassoon used prominently to create a dense, layered sound.

Perhaps the most famous part of the score is the opening movement of “The Adoration of the Earth,” the “Introduction.” The music begins with the bassoon solo, based on a Lithuanian folk song, âTu, manu seserÄlÄ.” As the music builds, the orchestra adds more and more instruments, creating a dense, swirling texture that suggests the chaotic energy of the natural world. As the ballet progresses, the music and choreography become increasingly frenzied and intense.

In “Dance of the Earth,” the final movement of “The Adoration of the Earth,” for example, the dancers move in a wild, uncoordinated manner that reflects the chaotic energy of the music. Dancers rush about, bumping into one another, flailing their arms. The music itself is marked by sudden shifts in tempo and mood, with abrupt changes in rhythm and melody that keep the listener off-balance.

The story of “The Adoration of the Earth” follows the sequence of 1) an elderly soothsayer prophesying the start of spring in the movement “Augurs of Spring,” 2) a ritual abduction dance and the khorovod, the ancient Slavic circle dance, performed in the “Ritual of Abduction” and “Spring Rounds” movements, 3) a faux battle in the “Ritual of the Rival Tribes,” and 4) the introduction of the elders and the Sage in the “Procession of the Sage,” who becomes the central figure of the “Dance of the Earth”.

In the second part of the ballet, “The Sacrifice,” the mood becomes darker and more ominous. The music is still marked by pounding rhythms and dissonant harmonies, but it is now punctuated by ominous brass and percussion accents that suggest impending danger. In the movement, “Glorification of the Chosen One,” for example, the music is dominated by a repetitive, syncopated melody that is interrupted by sudden outbursts of brass and percussion.

The movements of “The Sacrifice” show the anointing of a Chosen One, a girl in the khorovod who accidentally stumbles into the center of the circle. By glorifying this Chosen One, evoking the Slavic peoples’ ancestors, and placing the Chosen One into the hands of the elders, the story spills into its horrifying conclusion.

The final movement of the ballet, “Sacrificial Dance,” is perhaps the most famous. In this movement, the dancers perform a frenzied, ritualistic dance that culminates in the sacrifice of the Chosen One. As the sacrificial victim exhausts herself by dancing, she goes into a fit of seemingly random actions, jumping up and down repeatedly, falling down, getting up once again, holding her tired legs until she finally collapses, dying with a terrifying gasp. The elders pounce, lifting her up with a rising cadence of screeching strings leading into a final orchestral hit, which Stravinsky could only call “a noise.” The music of the movement is marked by thumping rhythms and atonal harmonies, but it also has moments of eerie calm and beauty, such as the haunting melody played by the solo bassoon near the end of the movement.

The music of The Rite of Spring is so evocative that it can be difficult to separate it from the ballet itself. The two elements are so tightly intertwined that they become one entity. The harsh, atypical music reinforces the strange, pagan nature of the story and the unconventional movements of the dancers. The result is a work that is both thrilling and unsettling, challenging audiences to reconsider their preconceptions of what ballet and music can be.

Despite its initial scandalous reception in 1913, The Rite of Spring has become a landmark work of 20th-century music and dance. Its influence can be heard in countless later works of classical music and beyond, and its impact on the development of modern dance cannot be overstated. The Rite of Spring has become nearly synonymous with primal power, as seen in Disney’s 1940 animated film, Fantasia. Excerpts from The Rite of Spring score the film’s depiction of the destructive creation of the world, opening with bubbling volcanoes, continuing to the birth of life in the ocean, then to a bloody battle between two dinosaurs, and finally finishing with the K-T extinction asteroid wiping the dinosaurs away.

The Rite of Spring remains a testament to the power of music to bolster and amplify the emotional impact of other art forms, and a landmark achievement in the history of ballet and music alike.

March 1, 2023

Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Mythology

Written By Aditya Shivaswamy

Starting with droning strings, each piling onto another until the orchestra’s horns pull through, signaling lift-off, “The Ride of the Valkyries” is one of the most recognizable pieces of classical music. Ubiquitous in pop culture for its martial and awe-inspiring effects, as in Apocalypse Now, where the piece scores a soaring American military helicopter attack scene, “The Ride of the Valkyries” first appeared as a third act prelude in Richard Wagner’s opera Die WalkĂŒre, the third in a set of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Also known as the Ring Cycle, the opera cycle is a monster, a piece of music so epic and grand that it takes over 15 hours to stage. Fitting its monumental scale, the plot of the Cycle focuses on the machinations, struggles, and, ultimately, the destruction of the Germanic gods. The central object around which the rich cast of monsters, heroes, and deities revolve is the title ring, a cursed object that fosters jealousy and envy in those who hold or wish to hold it. (Sounds familiar? Tolkien and his Lord of the Rings universe owes a great deal to the Cycle, though Tolkien would adamantly deny any inspiration from it). Both Wagner and Tolkien, however, derived their masterpiecesâ stories from ancient Germanic and Norse sources.

Wagner was interested in the folk tales of his native Germany, believing them to contain universal themes that applied to the society of his times. Wagner saw corruption and moral degradation in contemporary culture and looked to Norse sagas and Germanic epics for answers. These sources included: (i) the 13th century Icelandic politician and writer Snorri Sturlusonâs Prose Edda, a textbook with a Christian interpretation of Norse mythology, (ii) the Poetic Edda, a 12th century collection of religious and minstrel Nordic poems; (iii) the Völsunga Saga, a pre- 11th century saga about the rise and fall of the Völsung clan (the clan of the hero Sigurd) and, in a starring role, the ring Andvaranaut; (iv) the ĂiĂ°reks saga, a 13th century Norse chivalry tale about King ĂiĂ°reks (Dietrich) and his heroic escapades; (v) and the Nibelungenlied, a Germanic poem about the Nibelung royal clan, the warrior-queen BrĂŒnhild, and the hero Sigfried. Wagner voraciously read treatises like the German intellectual Jacob Grimmâs Deutsche Mythologie that appeared out of the German Romantic movement which Wagner would be musically associated with later.

Wagner’s use of these mythological elements allowed him to create a rich, complex world that was full of symbolic meaning. For example, the Ring itself symbolizes the corrupting power of wealth and the dangers of unchecked ambition. The timeless and universal story of the Ring also explores the idea of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, as well as the eternal struggle between good and evil. The character of Alberich, the Nibelung king who renounces love in order to gain power to forge the Ring represents the destructive power of greed and the consequences of putting personal desires ahead of the greater good. Wagner also used the stories of gods, especially Wotan, the king of gods, to explore the themes of power, ambition, love, and redemption. Wagner was fascinated by the stories of gods and their struggles for power, and he used these themes to create a powerful narrative that resonated with audiences of his time. By analyzing all of these mythologies, Wagner crafted a potent distillation of pure, universal themes, the central focus of structural anthropology. As the anthropologist Claude LĂ©vi-Strauss stated, Wagner is “the incontestable father of the structural analysis of myths.” However, Wagner didnât dwell on those themes, instead mined them for use as the leitmotif in his operas.

The leitmotif is defined as a recurrent musical theme that is associated with a person, thing, or, more importantly, an idea. The leitmotif existed prior to Wagner, but Wagnerâs extensive and virtuosic use of the technique in his works led the word to be inextricably linked to him. By linking a universal thought or emotion with a character or event by way of a leitmotif (some describe joy and love via the goddess Freia; freedom and heroism via Siegfried; and womanhood and love via BrĂŒnnhilde), Wagner layered his music with multiple leitmotifs to create a new, syncretized emotional narrative from existing mythologies. In short, Wagner created his own mythology.

Wagner began work on a new mythology early in his career. Starting in 1848, 21 years before the first opera of the Ring Cycle was ever premiered, Wagner wrote two large works, a prose named The Nibelung Myth as Draft for Drama, and a poem named Siegfriedâs Death. Wagner didnât simply summarize the Nibelungenlied or the Volsung Saga. Instead, he changed many aspects of the myth, drawing inspiration from philosophical treatises like Arthur Schopenhauerâs The World as Will and Representation and political and revolutionary texts by Wagnerâs friend, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. In 1848, Wagner got politically and philosophically radicalized under the influence of a series of revolutions sweeping Europe, now called the Revolutions of 1848. (Wagner would identify with many different ideologies in his life, like anarchism, socialism, nationalism, and finally, fascism). These revolutions were anti- monarchist, populist, and liberal in nature, perfect for the Romantic and polemical Wagner. Wagner actively took a role in the May Uprising in Dresden, publishing incendiary revolutionary tracts. Once the Saxon monarchy retook Dresden, Franz Liszt helped Wagner flee Germany. The events of 1848 and 1849 forever changed Wagnerâs Ring Cycle. There are similarities between the Aesir Gods, who are overthrown and whose palaces are burnt to the ground at the end of the Cycle, and the power-hungry, old-fashioned German monarchs that Wagner was trying to depose. Later, Marxists like George Bernard Shaw would claim that the Cycle was about the collapse of capitalism, with the dwarf king, Alberich and his industrial, slave-driven world Nibelheim serving as a plutocrat.

Whatever the political basis of the Ring Cycle, these early drafts show that Wagner was trying to create a new, updated, universal mythology for the modern age. The Ring Cycle continues to be celebrated today, transcending the various ideologies that Richard Wagner, the man, held. The sheer power of the story, coupled with actual music (which would necessitate an entirely new blog post), ensures that Der Ring des Nibelungen will be remembered long into the future.

February 8, 2023

Boléro Unraveled

Written By Audrey Timoszyk

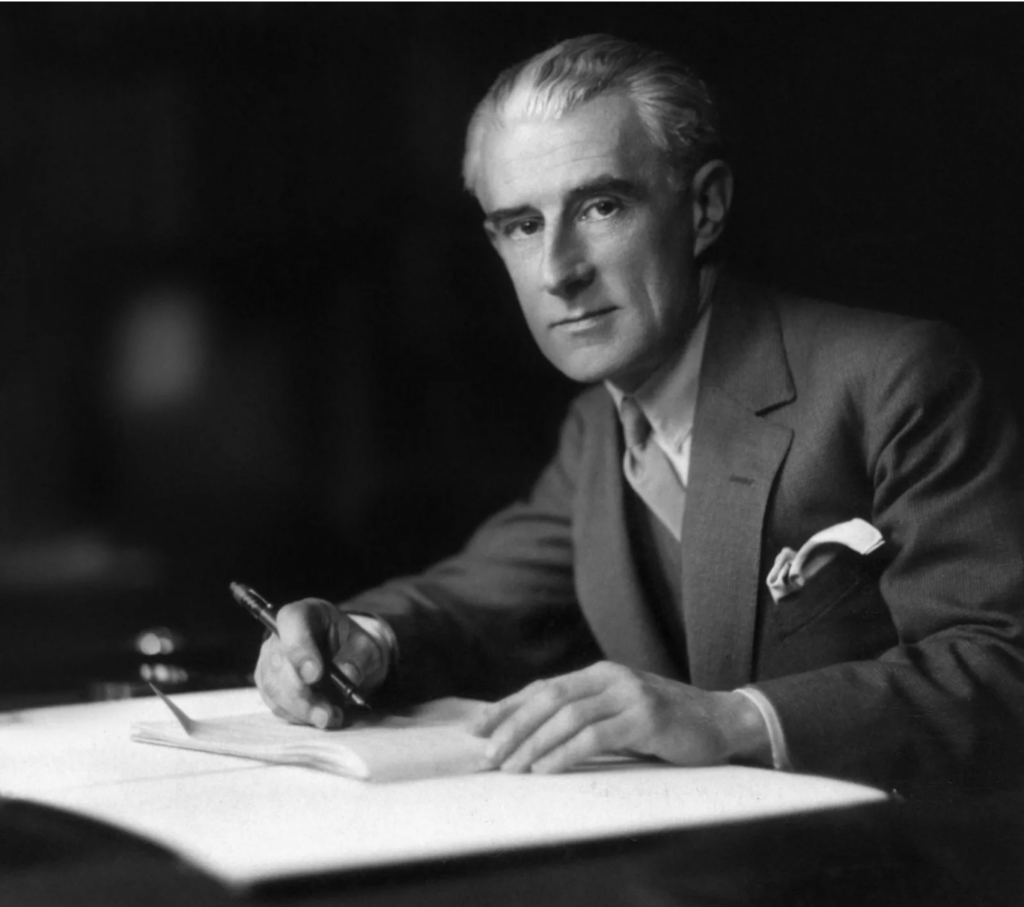

It starts with a snare drum that quietly taps the rhythm that will be present throughout the piece. The melody then opens up with a flute solo, and over the course of fifteen minutes, other instruments add into the melody. Finally, the orchestra reaches the very top of the longest crescendo ever written, and the two-phrase theme ends with a bang. BolĂ©ro is quite possibly Ravelâs most famous work, yet itâs so different from everything Ravel had ever written up to that point. It turns out that there may be a psychological reason behind the repetitiveness of Ravelâs BolĂ©ro.

To fully understand how BolĂ©ro is different from Ravelâs other works, we have to look at some of the characteristics of Ravelâs style. Ravel was a French impressionist, and with this title comes a very unique type of music. French impressionistic music is often very colorful, with small melodic snippets, unlike the long and developed Romantic period melodies. It also usually lacks a consistent pulse and is mostly atmospheric, with the goal of creating a very specific mood. There often is very little, if any, singable melodic content. Notably, not much is developed throughout the course of the entire piece. To create the kinds of colors present in French impressionism, composers will often use quick runs or scales, trills, and dramatic crescendos or decrescendos, contrasted with semi-melodic long notes or melodic phrases. A combination of these in an orchestral setting across many different instruments produces French impressionismâs characteristic âwash of colorâ. This âwash of colorâ approach is evident in many of Ravelâs compositions, most obviously Daphnis et Chloe. However, versions of these âcolorâ techniques can be seen in his other works, like Ma Mere LâOye.

Now, back to BolĂ©ro. Immediately, the listener is hit with the snare drum, otherwise known as a consistent pulse. Then, the flute solo comes in with singable melodic content that gets developed throughout the entire piece. There are no âcolorâ effects in the other instruments, they just continue the melody as the piece goes on. See it yet? Almost none of the techniques that are normally present in Ravelâs music exist in BolĂ©ro. Ravelâs characteristic sound is completely absent.

So, what changed? How did Ravel go from Daphnis et Chloe to BolĂ©ro? The answer may come from a surprising source: at the time of BolĂ©roâs composition, Ravel was suffering from frontotemporal dementia. This type of disease is caused by the degeneration of cells in your frontal cortex, which is the area of the brain just behind your forehead. The specific area that was degenerated in Ravelâs brain was the same area that had to do with language. Ravel did, eventually, lose his speech completely. However, the weird thing about losing language is that the language circuit also affects other circuits in the brain. Most importantly, because the language circuit is kind of a check for repetitive behavior and the daydreaming circuit, loss of language also leads to an explosion of intense visual experiences. Basically, because language inhibits this constant stream of visuals, and frontotemporal dementia turns off the language circuit, visuals are able to run wild. And since the circuit that deals with repetitiveness is also always on, these visuals are usually repetitive and mechanical.

Hereâs where BolĂ©ro comes in. The repetitiveness of BolĂ©ro may very well come from Ravelâs drive to repeat the same idea, the same phrase, the same melody over and over and over again in an obsessive pattern. BolĂ©ro was the result of Ravel trying to express the torrent of images that were suddenly sweeping over his consciousness. And so, in BolĂ©roâs repetition, in its constant restatement of a single idea, a dying man found comfort. He found a place to express what was going on inside of him, he found an escape from his disease, and most importantly, he found a melody that has stayed with mankind almost one hundred years after his death.

Special thanks to Radiolab. You can find the original story here at https://radiolab.org/episodes/unraveling-bolero

October 31, 2022

A Whole New World: Guide to DvoĆĂĄkâs Ninth Symphony

Written By Deepali Kanchanavally

AntonĂn Leopold DvoĆĂĄk was a Czech composer in the Romantic period, known for incorporating elements of folk music into his writing, and was one of the first Czech composers to gain worldwide recognition. Many of his most famous compositions were written during his time in America.

DvoĆĂĄk traveled to America in 1892 after being hired as the director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City. The school was created in an effort to bring about more American-styled musical education and training. Reluctant at first, DvoĆĂĄk eventually agreed to make the journey and stay in America for three years. In my opinion, he wrote some of his best music during his stay in the United States, including the Cello Concerto in B Minor, the American Quartet, and his Ninth Symphony, more commonly referred to as the âNew World Symphony.â

The inspiration behind this symphony is quite interesting. It was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic during DvoĆĂĄkâs stay in America. He took it as an opportunity to incorporate American musical characteristics and styles into European music. Being a nationalist composer, DvoĆĂĄk decided that the best way to capture the American spirit was to explore elements of native groups in the country. He believed that the richest music came from the Native American and African American folk songs.

âThe music of the people is like a rare and lovely flower growing amidst encroaching weeds. Thousands pass it, while others trample it under foot, and thus the chances are that it will perish before it is seen by the one discriminating spirit who will prize it above all else. The fact that no one has as yet arisen to make the most of it does not prove that nothing is there,â DvoĆĂĄk stated.

He was heavily influenced by the music he heard from one of his students, Harry T. Burleigh. Burleigh was an African American singer, who shared some of his native music with DvoĆĂĄk. When listening to the first movement of the Ninth Symphony, you will hear similar musical ideas to those used in âSwing Low, Sweet Chariot,â an African American folk song sung to him by Burleigh. Lots of the rhythms and musical figures seen throughout the symphony can be traced to folk music.

I admire the fact that DvoĆĂĄk looked beyond the middle and upper class residents to find the music that he felt truly represented America. I think being a nationalist composer had a significant impact on his search for inspiration as well. He strived for all people in America to be well-represented through his music.

Now, letâs take a closer look at each individual movement of the symphony.

The first movement, Adagio-Allegro molto begins by introducing the E minor key with a slow melody. The melody gets passed around to multiple instruments, using a call and response format. To me, the beginning of the first movement sounds quite nostalgic, almost like DvoĆĂĄk is looking back to his homeland. As the movement progresses, he includes more brass and percussion to bring a powerful color change. These changes and transformations in the movement are similar to those of a Czech polka dance, demonstrating DvoĆĂĄkâs nationalistic style. Of course, throughout the movement, DvoĆĂĄk incorporates themes and styles from âSwing Low, Sweet Chariotâ. If you havenât heard it, I would encourage you to listen to a recording and compare it to the first movement of the Ninth Symphony because it is really amazing how you can hear the similarities in the melodies.

The second movement, Largo, is the most famous movement of the symphony. Throughout the movement, you can hear DvoĆĂĄkâs homesickness and reminiscing of his homeland. I especially love the chord progression at the beginning of the movement because it sounds so powerful and deep yet gentle. This movement contains the famous cor anglais (English horn) melody. Throughout this melody, you can hear the influences of spiritual music, as DvoĆĂĄk uses a pentatonic scale. Native American music commonly uses this type of five-note scale.This movement was also influenced by a poem DvoĆĂĄk read, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s âThe Song of Hiawatha.â The excerpt he read described Hiawathaâs journey across the plains of America with his wife. The chords from the beginning are passed to the winds and the strings play a variation of the cor anglais melody. Towards the end of the movement, chords from the first movement show up again. I really love this movement because of the heartwarming melodies that DvoĆĂĄk uses. Also, the call and response, as well as the passing around of the melody, introduces more color and depth to the movement. DvoĆĂĄkâs skill lies in making the transitions sound natural and unforced.

The third movement, Molto vivace, was influenced by a scene depicting the Native Americans dancing in âThe Song of Hiawatha.â We can see the influences of the poem, as the movement has quite an upbeat and festive nature to it, and the Ÿ time signature helps emphasize this. Along with native influences, Beethovenâs Ninth Symphony also influenced this movement. It is certainly a great way to lead up to the ferocious fourth movement.

Finally, we arrive at the bold fourth movement, Allegro con fuoco. This movement brings back quite a few elements from past movements as well as introduces new ideas. DvoĆĂĄk includes themes from Czech music as well as Native American and African American music. The powerful brass melody along with the emphatic supporting strings make this movement pop. It is a great climax due to the accents and variety of dynamic and color changes. The end of the movement is very powerful and booming and majestic, which is due to the vibrant chords and all of the energy produced by each section of the orchestra. I feel like DvoĆĂĄk did an amazing job summing up all of the past ideas in the symphony as well as maintaining a fiery atmosphere throughout this movement.

In the âNew World Symphony,â DvoĆĂĄk took such a unique approach to representing American music, as he dug deep to find its roots. It was a great model for future music using folk melodies. It is astonishing how he was able to make the perfect blend of European music and American music without sounding unnatural. It is no surprise that the symphony is considered one of DvoĆĂĄkâs best works.

September 27, 2022

Joyce DiDonato, Living the Classical Life

Written By Audrey Timoszyk

âThe fire you have to walk through will be one of the greatest strengths you have,â said Joyce DiDonato in an interview with Living the Classical Life (DiDonato). Joyce DiDonato is an accomplished mezzo-soprano who has won multiple Grammy Awards, the 2018 Olivier Award winner for Outstanding Achievement in Opera, was the 2019/20 Perspectives Artist for Carnegie Hall, and many more achievements. In her quote, DiDonato was talking about an experience she had with another opera singer who was judging a competition DiDonato was a part of. DiDonato said she âwas singing to express and connect and communicateâ during this competition. Like any artist, during the competition, she put herself out there. And when DiDonato finished her song, the judge told her an earth-shattering truth: âyou have nothing to offer as an artist.â

How do you recover from that? How do you recover when you put so much into your music, and someone who has your respect tells you that you have nothing to offer artistically? How do you recover when you offer up a piece of yourself and someone tells you that you are worthless? Joyce DiDonato was hurting from this comment in multiple ways. The Houston Grand Opera was taking her off of a lead role, and just when she felt like her career was coming together, this comment came and shook everything up. DiDonato said she had to realize that her judge âwasnât an evil personâ and wasnât âjust interested in torturing [her]â (DiDonato). DiDonato had to step back. She thought, âOkay, letâs be practical about this. Why would [the judge] say it? I was well prepared, I was singing well, IâveâŠâ(DiDonato). And it âstarted to dawn on [her]â (DiDonato). This âwas a song competition, so even more of a sort of sacred space about how youâre supposed to be as a singerâ (DiDonato). DiDonato realized something. She âwas perfectly coached, was perfectly prepared, [she] was perfectly trimmed and proper. And [her] hair was what an opera singer [was] supposed to look like, and [her] dress was just artsy enough but conservative enough.â DiDonato âarrived [at the competition] like a caricature of an opera singer, and [her] hand was on the piano and everything was correctâ(DiDonato). And then DiDonato saw what her judge had seen. She thought, âMy God, [the judge] was right. Iâm not saying anything as an artist. Iâm regurgitating what Iâm supposed to do according to the conservatory and according to the coachesâ (DiDonato). And DiDonato decided, âwell, thatâs the last time anybodyâs gonna be able to say that about me, and I had better go figure out what it is that I have to say [as an artist]â (DiDonato).

I think many of us, especially as young musicians, fall into the same trap Joyce DiDonato did. We worry so much about pleasing our teachers and judges by playing what is on the page perfectly. We spend hours and hours dissecting every run, and using a metronome to avoid compressing the notes or rushing, and analyzing every imperfection in our playing, that we forget why we fell in love with music in the first place. I remember preparing Chaminadeâs Concertino for a solo competition, and while I was practicing, I played a B natural instead of a B flat. And like any good student, I marked that B flat. But the whole time I was thinking, âOh my God. If I canât even remember the key signature, how in the world can I expect to play this piece well?!? Iâve been practicing this piece for months, and the competition is in just two weeks, and I canât even remember to play a B flat, and I am SO screwed, this is NOT going to go well, Iâm going to get up there and play fifteen B naturals instead of B flats, and itâs going to sound horrible, and Iâm going to get a terrible score in the competition, and Iâm going to disappoint everyone who worked so hard to help me prepare for this. How can I do this???â I was so concerned about making Chaminadeâs Concertino technically correct and playing all of the right notes that I forgot about the music. I forgot why Chaminade wrote it and why I was playing it: to express ourselves as artists. Beethoven said it best: âTo play a wrong note is insignificant; to play without passion is inexcusable.â

Joyce DiDonato had to walk through the âfireâ of someone telling her that what she stood for as an artist and opera singer was worthless. However, she ended up shaping her entire artistic career off of this comment, and even considered it a blessing. I think we can all learn something from her experiences: no matter what we do, whether itâs music or carpentry, we need to remember why we do it. Whenever we do something, we need to remember our purpose in doing it, and always stay true to that purpose. And if weâre able to do that, maybe we can win multiple Grammy Awards, the 2018 Olivier Award winner for Outstanding Achievement in Opera, and become the 2019/20 Perspectives Artist for Carnegie Hall.

Go check out the whole interview below.

âThe fire you have to walk through will be one of the greatest strengths you have.â – Joyce DiDonato

MAY 18, 2021

BTS, “Black Swan”

Written By Seo Young (Youngee) Ha

“A dancer dies twice â once when they stop dancing, and this first death is the more painful.”

Korean artist BTSâs 2020 single âBlack Swanâ opens their music video with this quote by TIMEâs greatest dancer of the 20th century, Martha Graham.

The track opens with a suspenseful orchestra and incorporates plucking sounds of the traditional Korean instrument, gayageum, and remains consistent throughout the entire song. The ambiance created by the deep tones of stringed instruments complements the message carried in the song.

Martha Grahamâs quote proposes that a dancer feels purposeless when they can no longer express themselves through dance. Similarly, in âBlack Swan,â BTS writes that the day music no longer resonates and fills them with passion, it will feel like death. Leader of BTS RM raps the lyrics, âIf this canât make me cry anymore, if this canât make my heart tremble anymore, maybe Iâll die like this. But what if that momentâs right now, right now.â BTS captures the ice-cold dread that many artists fear: when their passion feels like a job rather than a love. They write of the âblack swanâ that lives within them and every artist. This swan is the daily inner thoughts of a performer.

Along with these lyrics, different melodies and harmonies from strings are intermingled with one another to create a sense of melancholy. As the instruments build up to the chorus, there is a sudden explosion of powerful music. The listener can almost visualize the swan flying free from its fears. The instrumentals soon slowly die down as the swan is dragged from its freedom and back to doubt and guilt. This repeats a couple of times in the track, and I interpreted it as the constant struggle an artist experiences with losing their passion.

âBlack Swanâ is a song to be dissected, analyzed, and listened to over and over again. At times I feel nostalgic and at others, I feel fear. Every time I listen to it, I discover new wordplay or metaphors. BTS speaks of a very real and painful phenomenon that performers either learn to conquer or inevitably submit to. I am reminded of my own struggles with keeping my passion close to my heart and never submitting it in exchange for capital greed. Everyone can have a different interpretation of this piece, and it is a great example of pop music fusing with elements of classical to invoke emotion in listeners across the world.

MARCH 4, 2021

Muddle Instead of Music

Written By Ethan Hynes

Before you read, I encourage you to listen to Shostakovichâs 8th String Quartet. The less you know before you listen, the better.

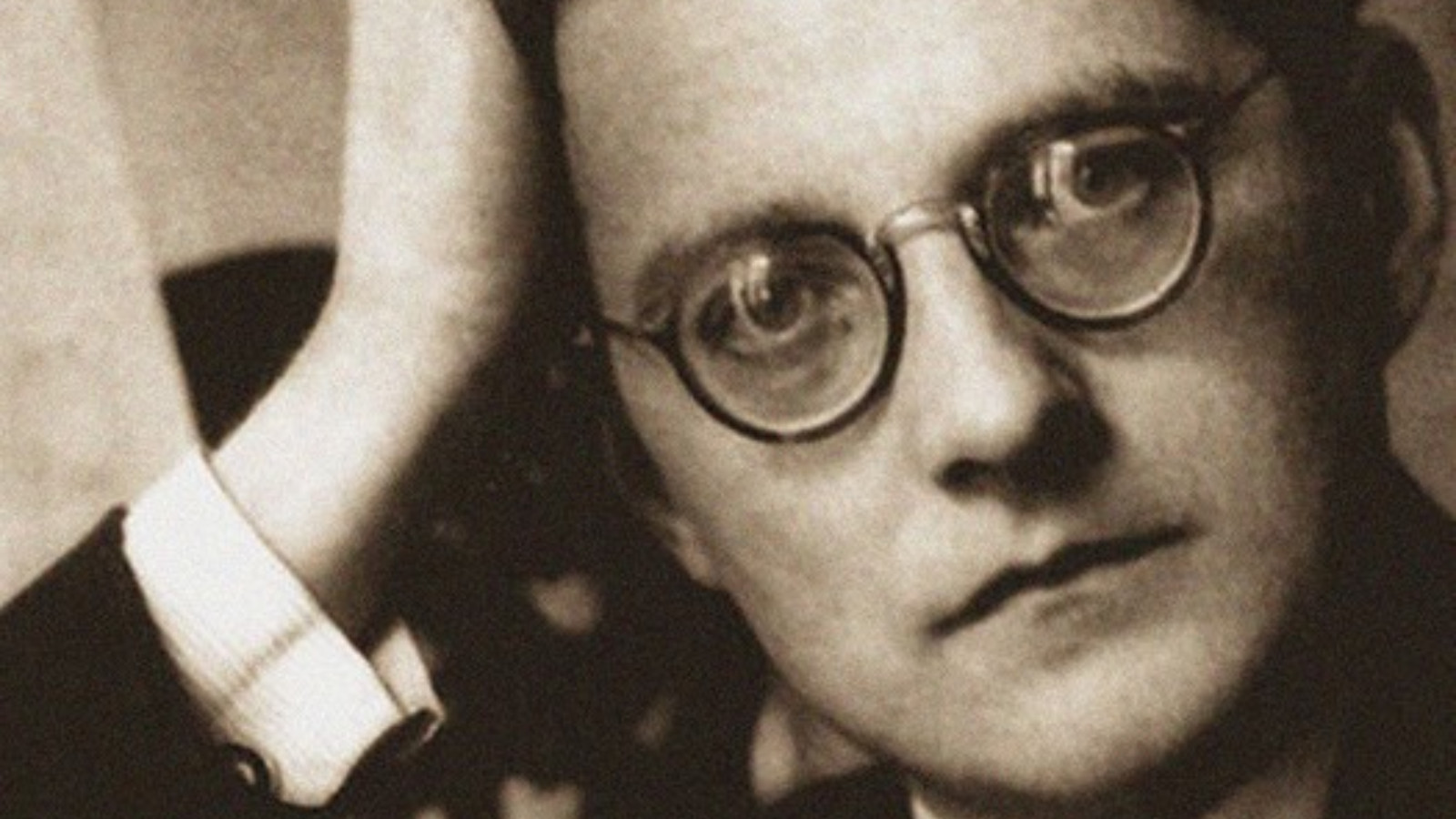

Introduction:

On January 26th, 1936, Joseph Stalin saw Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, a well-received opera by up and incoming Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich. On January 28th, 1936, the official newspaper of the communist party, the Pravada, published a tirade of Dmitri Shostakovichâs opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. It was titled âMuddle Instead of Music.â Again on February 6th, the Pravada attacked Shostakovichâs ballet The Limpid Stream. This series of events is now known as Shostakovichâs first denunciation and the beginning of Shostakovichâs lifelong struggle with censorship under a repressive regime. Context is crucial with Shostakovich. Understanding what was happening in his life when he wrote a piece of music illuminates so much more meaning onto the piece itself. Of course, this is a general rule applied to almost every composer, but Shostakovichâs environment made understanding context even more significant. This is made clear by his numerous self-quotations and references to other composersâ music throughout many of his major and minor pieces. This has led to musicologists attempting to understand and interpret Shostakovich’s music, using his self-quotations as clues to what he was trying to communicate. Perhaps the most famous example of this would be his Eight String Quartet. Before I talk about the music itself, the context must be given.

Context:

In 1960, Shostakovich joined the Communist Party to take the role of General Secretary of the Composersâ Union. However, this was no easy task for Shostakovich. His son, Maxim, recalls this event bringing a usually stoic Shostakovich to tears. He even claims that Shostakovich told his wife that he had been blackmailed into joining the party. Russian musicologist and friend, Lev Lebedinsky, even claims that Shostakovich was suicidal. Once he joined the party, many articles and denunciations he had not written would be published under his name in the Pravada. In response to being forced to join the communist party, Shostakovich wrote his Eighth String Quartet.

The String Quartet:

The twenty-minute, five-movement quartet flies through a range of tempos, tones, and quotations until it slowly dies in its final movement. The first thing you hear is the cello play a four-note motif (D-Eâ-C-B) that the rest of the quartet is built on. Commonly called the DSCH motif, this is Shostakovichâs musical signature. Any piece that uses this motif is autobiographical in some way. The first movement opens in a painful largo that quotes his First and Fifth Symphony. The pieceâs tone quickly changes into a distressed allegro molto, sporadically echoing the DSCH motif and his own Piano Trio No. 2. The third movement maintains a higher tempo but regains composure leading the listener through quiet passages that build and suddenly fall off. In this movement, he quotes his Cello Concerto No. 1, another highly auto-biographical piece. Following this, his fourth movement opens with a slow, heavy three-note âbangingâ motif. It is theorized to be symbolic of the government knocking on his door. Also, in this movement is the most direct communication of the composerâs feelings. He quotes the aria from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and a revolutionary era song called âTormented by Grievous Bondage.â If it wasnât already clear, Shostakovich is writing about himself and is in extreme turmoil. In the final movement, Shostakovich maintains a slow, powerful tempo and builds on themes from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, as he did in the previous movement. The DSCH motif is also extremely prevalent in this movement, similar to the first. The quartet quietly falls into silence.

The Connection:

Officially, this quartet is dedicated âto the victims of fascism and the warâ but it is clear that this piece is also heavily about Shostakovich. Lev Lebedinsky was Shostakovichâs friend, and his claim that Shostakovich was suicidal is not a stretch of the imagination. It is easy to see how Shostakovichâs Eighth String Quartet could have been his musical suicide note with this context. Itâs a grim thought but it makes sense. Many of the melodies are based on his auto-biographical DSCH motif. He quoted many of his most famous and influential pieces, including the work that began his fight with the Communist party. Listening to this piece as a suicide note brings it so much more power. You feel his despair and hysteria. Understanding this pieceâs context completely changes how itâs listened to and how the listener is affected by it. Context is crucial.

Conclusion:

In April, 2020, I had to write a paper on a piece of my choosing for my Orchestra class, and I chose the Eighth String Quartet. I had listened to it quite a bit before then, but I had never really researched it deeply. After I studied it and listened through it again, Iâll be honest, I was in tears. I felt like I understood Shostakovich and the feelings he felt when he wrote the piece. It was so powerful, and sometimes I still get teary-eyed listening to it. Since then, I have begun researching every piece I listen to, and I have spent more time trying to understand the music I consume. With everything I have written here in mind, I implore you to listen to this string quartet again and look for every DSCH motif and quotation you can. I understand if Shostakovich or this quartet just isnât your thing. I wonât try to convince you to like it but please research the music you love. Try to understand your music. The more you put into listening, the more you will get out of it.

DECEMBER 8, 2020

Music and Stress

Written By Sophia K. Mohamed

We are living in a very stressful time and change can be overwhelming. People are trying to adjust to a new way of life during this pandemic. A way to win the battle with stress is music.

In a study by the U.S. National Institute of Health, listening to music affects the autonomic nervous system, which can lead to less stress.[1] Some rhythmic patterns found in music can stimulate you both physically and psychologically, creating an essential harmony and improving your well-being. It enables the alpha waves in your brain, boosting endorphins and dopamine, which can lead to relaxation and confidence.

Different types of music can make you feel other emotions, and not all music can boost your persona. Scientists performed many studies and found that classical music has the most significant positive effect on your psychological basis. Classical music is proven to lead to improved sleep, reduced stress, better memory, lower blood pressure, and higher emotional intelligence. Have you heard of parents using classical music to help a baby sleep? This is due to the Mozart effect! Melodic harmonies are very soothing, mimicking a lullaby, often times putting you in a state similar to meditation. Your body and mind can become at peace.

Check out my recommendations of classical artists to get you started on your stress-free journey:

Beethoven- FĂŒr Elise

Delibes â ‘Flower Duet’ from LakmĂ©

J.S. Bach â Toccata and Fugue in D minor

Johann Strauss II â The Blue Danube

Misha Goldstein – Piano Sonata No.8 in C Minor, Op. 13, “Pathetique”

Mozart – Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

Puccini â ‘O mio babbino caro’ from Gianni Schicchi

Ravel â BolĂ©ro

Saint-Georges- Symphony Op. 11, No. 1 in D Major

[1] Thoma, Myriam V et al. âThe effect of music on the human stress response.â PloS one vol. 8,8 e70156. 5 Aug. 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070156

DECEMBER 4, 2018

Classical Masterpieces and Artwork: From the stroke of a brush to the touch of a key

Written By Alexa Hassell

Looking for a new way to enjoy music or art? Try experiencing them together! Some of these pieces were inspired by paintings, some simply seem to emulate them; however, all four of these music and painting combos are best received together. Listening while looking (and vice versa) helps to inspire the senses in many ways, so try these suggested pairings, and then create a few of your own.

Katsushika Hokusaiâs The Great Wave off Kanagawa and Claude Debussyâs La Mer

This famous Japanese woodblock print adorned the wall of Debussyâs studio. It, along with childhood memories of visits to the seaside, are said to have inspired Debussy to compose La Mer. A rich depiction of ocean scenes full of impressionistic and daring harmonies, this composition would inspire many films scores to follow. Called âthree symphonic sketchesâ, La Mer starts with a depiction of the ocean as dawn becomes midday, moves to a play of the waves, and then finishes with a dialogue of the wind and sea. Two powerful movements, framing a lighter middle, eloquently complete the concept of a rushing wave that Hokusai portrays so beautifully in his painting.

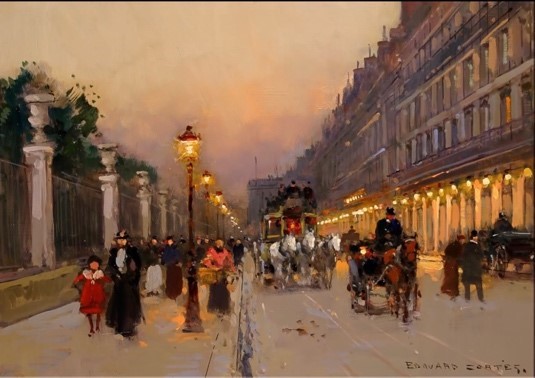

Edouardo Cortesâ Rue de Rivoli and Eric Satieâs GymnopĂ©dies

Two creators with a focus on the same inspiring city makes for a perfect pairing. Satieâs piano composition seems a nostalgic nod to the trials of everyday life in the large and illustrious city of Paris, where motion is constant and sounds are widely varying, yet he also implies a contentment with this lifestyle. The ease and rhythmic tones match the warm colors and elegance of Cortesâ work. Whether it be walking, riding, or driving, the citizens of Paris are peacefully aware of their bright world, so inspiring to artists of all types.

Edgar Degasâ The Dance Class and Frederic Chopinâs Etude Op. 25, No. 11 (âWinter Windâ)

Upon hearing this Chopin composition, I immediately thought of a dance studio where ballerinas effortlessly perform, leap, and pirouette across the floor. Degas is arguably the most famous painter of dance scenes, and therefore, the pairing seemed obvious. The image Degas provides and the tone Chopin suggests are similarly – and confidently â portrayed. Listening to one while admiring the other makes for an enhanced artistic experience. If you are looking for a lighter, more fun partnership, then these two pieces are exactly what you are looking for.

Arnold Böcklinâs Die Toteninsel (Isle of the Dead) and Sergei Rachmaninoffâs Isle of the Dead

Sharing both a title and a sense of urgency, these works have left an enduring cultural legacy. Rachmaninoff composed his piece after viewing Böcklinâs painting in France in 1907. Though the artist created multiple versions of this same scene, all contain the same mourning white figure and coffin. The image is so compelling it found its way into several important films over the past century (the most recent being Alien: Covenant), and has inspired multiple compositions, from classical to heavy metal. The most famous of these is the ominous symphonic poem from Rachmaninoff, which illustrates the foreboding brilliantly, and serves as a warning to any listener who comes across this scene.

OCTOBER 27, 2017

Beethoven: The Somewhat Informed Guide

Written By Brian Le

Have you ever wondered how to approach classical music without being overwhelmed? Or perhaps you were lost during a conversation with your fellow musicians? Well, look no further because I, your classical classmate, am here to help you explore what you need to know.

Our first piece in the standard orchestral repertoire weâll be looking at will be Beethovenâs 5th Symphony in C minor. Ah, the infamous Da-Da-Da-DUMMM!

Many have heard the beginning of the piece throughout their lives as a sound effect, or perhaps a text tone, and some have listened to the entire first movement in animated movie, Fantasia. The piece was composed in a time of turmoil when Beethoven (in his mid-thirties) was slowly succumbing to deafness, and the world around him was in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars. In response, Beethoven chose to compose a symphony in a key that held special importance for him: C minor. He often used this key to convey stormy, tumultuous, and even victorious moods. C minor was the key of Beethoven the hero. He used it as a conduit for his strongest personal expression, uncompromisingly and even selfishly leaving the precise aesthetics of the Classical era behind, and diving, head-first, into the emotion-rich, unpredictable world of Romanticism.

But say youâre a seasoned musician, and youâve memorized the score to all four movements of Beethovenâs 5th. Not to worry, for Iâve got another masterpiece which may tickle your fancy. Beethoven wrote 16 string quartets, increasing in complexity and romantic sentiment from the first to the last. The Grosse Fugue (or Grand Fugue) was one of his last string quartets, and it successfully encapsulates the density of a multi-movement symphony within a 16 minute, single-movement chamber piece. I like to call the Grosse Fugue Beethovenâs âabsolute worst best pieceâ because, when it was written, musicians and critics alike deemed it âinaccessibleâ, âa mistakeâ, and âhis single most problematic composition.â But as time went on people began to realize its hidden beauty. The piece is ambitious and paradoxical, often leaving its listeners with more questions than answers. For me, this is the epitome of art being ahead of its time. Believe me, youâll feel it when you hear it.

I sincerely hope youâve added something to your Spotify playlist. Catch yâall next time where weâll take a look at the second B of the 3 Bâs, Johannes Brahms.

For further listening, please consider Beethovenâs Symphonies No. 3, 6, 7, and 9 as well as the Egmont Overture for your symphonic satisfaction, and any of his 16 String Quartets if youâre aching for some deep and beautiful chamber music.

NOVEMBER 6, 2017

Brahms: The Somewhat Informed Guide

Written By Brian Le

Welcome back everyone to the second installment of Listening to the Literature. As promised, weâll be looking at Johannes Brahmsâ music this week.

But first, some backstory!

For starters, Brahms was a bit of a controversial figure during the early Romantic era because his music relied heavily on the ideas and structures of the earlier, Classical era. Some thought of him as conformist, or even boring, while others praised his respect for, and continuation of, tradition. This reputation, along with his stubborn personality, an aversion to publicity, and deteriorating health towards the end of his life, led to his becoming something of a recluse; and many people, upon meeting him, felt he was unapproachable or cold.

His music, however, is by contrast very warm, and reflects his genuinely generous and kindhearted nature. With that said, letâs talk about some music!

Iâm sure youâve heard his Lullaby or Hungarian Dances, but Iâm starting us off with his Symphony No. 1 in C minor. The piece took Brahms over 21 years to finish, but boy did it make an impression when it premiered. Some think of it as âBeethovenâs Tenthâ because of how much the music recalls Beethovenâs grand and heroic sound. It reminded audiences that great symphonies â and symphonists – still existed, and it was clear that Brahms was a master of the form. The start of the piece practically shouts at the audience, demanding not be underestimated, with the timpani powerfully pounding away as solemn colors are painted by the strings. Keep an ear out for those hidden, yet stunning, oboe lines!

If thereâs one piece I love to death but canât elaborate too well on, itâs Brahmsâs A German Requiem. Itâs a grand, gorgeous, sultry choral piece with the power to move mountains and create lakes. All I can say is take my word for it.

For our chamber piece, which I think is where Brahms shines the brightest, look no further than his Clarinet Quintet in B minor, written for string quartet and clarinet. The piece was composed in 1891, a few years before his death, and heavily referenced Mozartâs clarinet quintet (from 1789) which had just reached its 100 year anniversary. Even though this was written well into the Late Romantic period, Brahms was still focusing on the form and structure of the Classical era, which the rest of Europe had moved on from long ago. Itâs hauntingly beautiful and somber, particularly in the 1st and 4th movements, where you can almost hear Brahms himself weeping through the clarinet and cello voices.

Thank you for reading as always! Next week, weâll be wrapping up the introduction of the series with the third B: Johann Sebastian Bach.

For further listening, please consider Brahmsâ Symphonies No. 2, 3, and 4 and the Academic Festival Overture for your symphonic satisfaction. For your chamber music needs, I recommend his Piano Quartet, Piano Quintet, String Quartets No. 1, 2, and 3, and String Sextet no. 1.

DECEMBER 4, 2017

Bach: The Somewhat Informed Guide

Written By Brian Le

Weâre rounding off the last B in the prolific 3 Bâs with Johann Sebastian Bach, or J.S. Bach for short. Make sure to include the âJ.S.â because there are 10 composers in the Bach Family and only one of them earned the title, âThe Father of Musicâ. I wonât delve too deep into the history behind his genius â thereâs a lot of theory, technicality, and historical context â so letâs just get started with some baroque music!

When I think J.S. Bach, I think Brandenburg Concertos. Bach wrote a total of six concertos as a body of work for Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg, with hopes that Ludwig would hire him as a musical director. Sadly, Bach received no response, but his pieces lived on to comprise one of the greatest orchestral sets from the Baroque era. They featured an unusually wide range of instrumentation for his time and raised the bar for the Concerto Grosso form. In the Brandenburg Concertos, the soloists and orchestra bounce off of each other masterfully with their own unique textures. Of particular note ate the 4th (which contains some of the most fun, virtuosic violin lines in the Baroque repertoire) and the 5th (which introduced the harpsichord as a solid soloistic instrument for concertos). The six concertos truly capture a wide variety of orchestral colors and feelings.

Bach didnât really compose Chamber music, at least not in the way we generally think of it today. String quartets have been created by rescoring movements from his four Orchestral Suites, but other than a number of duets and one obscure trio sonata, he inked precious few small ensemble pieces. So Iâll focus on his solo works for violin, cello, and keyboard, and recommend my personal favorites: Violin Sonata No. 2, for its hauntingly beautiful Andante movement, Cello Suite No. 5, for its dance of hopelessness and inspiration, and the entirety of The Well-Tempered Clavier. Whatâs The Well-Tempered Clavier? Well, it’s two series of preludes and fugues, one written in every key. The intention was to heighten a keyboard playersâ skills, and popularize temperament tuning along the way. I view this as Bach at his purest. One can hear the foundation of music theory as we know it, and also discover many of Bachâs most important musical innovations.

Thank you for reading! Bach canât be fully appreciated without understanding the context of his music so if youâd like to hear more about it, let us know!

For further listening, please consider the 4 Orchestral Suites, St. Matthew’s Passion, and the Goldberg Variations. For more intimate music, I recommend the entirety of his Violin Partitas, Violin Sonatas, and Cello Suites.

DECEMBER 15, 2016

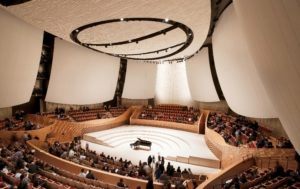

Eight Architecturally Beautiful Symphony Buildings

Written By Alexa Hassell

Orchestra Hall (Chicago)

Originally built in 1904, the Orchestra Hall in Chicago is unique in its exterior design. The outer facade does not hint at the hall sitting within. The architect was Daniel H. Burnham, a CSO trustee and Chicago architect, who complete the project at a total cost of $750,000. The facade is symmetrically built with pink brick and white limestone, and follows a Georgian style. Above the second floor, inscribed into a limestone band, are the names of five famous composers: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Wagner. The first floor entrance opens to the vestibule and main lobby. The main lobby leads to the main auditorium, which was designed in the Beaux Arts style. In 1950, Daniel Burnham, Jr. (son of the original architect) restored and redecorated the building, adding carpet to some floors, repainting spaces, and much more. Further renovations in 1966, brought modern technology and central air to the building. The pipe organ, which originally was created by Lyon & Healy (the largest instrument the Chicago-based company ever built), was installed early in 1905 and rebuilt by Frank J. Sauter and Sons in 1946. However, due to damage it had sustained during renovations the need to repair it was great. The organ was finally reinstalled during the summer of 1981 by M.P. Moeller, Inc. Final renovations to the building began in June of 1993 and were completed in 1997. These renovations resulted in a new music complex, a new restaurant, new offices, and new wall designs. In 1978, Orchestra Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places, making it a national landmark.

Walt Disney Concert Hall

The Walt Disney Concert Hall is located in Los Angeles, California, and home to the LA Philharmonic. It was designed by Frank Gehry, and opened in October of 2003. Lillian Disney, Walt Disneyâs wife, contributed $50 million dollars in 1987 so as to have a hall built honoring Waltâs love of the arts. The hall is considered to be one of the most acoustically advanced in the world. It is designed with a reflective stainless steel exterior, and an interior of mainly hardwood paneling. The walls and ceiling are finished with Douglas fir and the floor is finished with oak. Construction took over a decade due to the need to build of an underground parking garage first. The entire project cost $274 million dollars, with the parking garage alone accounting for $110 million of that. The concert organ on the inside was also designed by Frank Gehry with musical and acoustical insight from Manuel Rosales. After lots of back and forth, the final organ was made with curved wooden pipes by German organ builder, Caspar Glatter-Gotz. The concert hall also houses a famous restaurant owned by Joachim Splichal named Patina.

Morton H. Meyerson Concert Hall

The Meyerson, which is located in Dallas, Texas, is home to the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. It also houses two restaurants, multiple meeting rooms, and one of the most acoustically acclaimed halls in the world. It opened September 1989 after being designed by architect I.M. Pei. The name of the hall comes from the former president of Electronic Data Systems and former CEO of Perot Systems who was an avid supporter of creating a home specifically for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. The exterior of the building is mainly glass, metal and stone to set a contrast to the inside of the hall which is very traditional and include the extraordinary Lay Family Concert Organ. The uniqueness of the hall lies in its construction, with 74 concrete doors located at the top most parts of the hall which can open and close to accommodate the exact amount of reverberation desired for each concert, 56 acoustical curtains to diminish vibrations, and a hanging acoustic canopy (which can be lowered, raised, or tilted to reflect sound out into the hall more precisely). The resulting sound is unrivaled in its elegance.

Alice Tully Hall (Lincoln Center)

Alice Tully Hall houses hundreds of performances each year, ranging from dance to film to music. Its location, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, provides a busy and stimulating experience when visiting. Tully Hall gets its name from Alice Tully, a New York performer and philanthropist whose donations helped build the hall. The building itself belongs to the Juilliard School and was designed by Pietro Belluschi. It was built in 1969 and underwent renovations in 2009 as part of the Lincoln Center 65th Street Development Project. Housing the newest technologies and a great view, it has a three-story glass lobby and a sunken plaza. The building contains 10 floors (some of which are underground), three Juilliard theaters, Alice Tully Hall, 15 dance, opera and drama studios, three organ studios, 84 practice rooms, 27 classrooms, 30 private instruction rooms, rehearsal rooms, costume and scenery workshops, a library, a lounge, a snack bar, and administrative offices. Tully Hall is designed with wood batten (with dampening behind), lavender carpet, and an expanding stage. After renovation, a cafe and mezzanine level were added, and muirapiranga wood and limestone were added to the materials. The hallways leading up to the hall and the performance hall itself are both very aesthetic and stimulating. There is also a Swiss-made pipe organ inside the Hall. Its closeness to the subway required the building of extra supports and walls to prevent sound transfer.

Fisher Center

The outside of the Sosnoff Theater looks very similar to the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is due to the same architect (Frank Gehry) working on the project. The entire center opened in 2003 after three years of construction and $62 million dollars, and is located on the campus of Bard College in upstate New York. The buildingâs exterior is constructed of curved stainless steel and concrete. The interior contains the Sosnoff Theater, the LUMA theater and multiple studios. The Sosnoff Theater itself is quite distinctive: it includes a proscenium stage with a concert stage insert (this way concerts of drama, dance, and music can all take place), a hexagonal shape with walls that curves slightly inward to diffuse sound, and a high ceiling. With balconies and a crescent seating style, the feel of the hall is very intimate. The buildingâs system of air and heat are powered by geothermal sources which means the building is powered without the use of fossil fuels. The building is used mainly for school purposes (such as performances and graduations), but the Bard Music Festival takes place here as well. Many people have raved that this hall is the best acoustical and performance hall found in any small college.

Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts

Located in the heart of Kansas City, Missouri, the Kauffman center is home to the Kansas City Symphony. There are two theaters within the building: the Muriel Kauffman Theater and Helzberg Hall. The idea for such a building came from Muriel Kauffman, who first introduced the thought in 1994 with her family. Sadly, Muriel died in 1995, but nonetheless her daughter kept the project going as head of the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation. In 1999 the land for the center was purchased by the Foundation. The chosen architect was Moshe Safdie who designed the very first sketch in 2000 on a table napkin, and in October of 2006 ground was broken for the center. The building itself took nearly 5 years to complete and is made mostly of glass, concrete and steel cables. With two vertical and concentric arches and one shared backstage, the buildingâs structural complexity is its defining factor. The Kauffman Center also maintains educational programs that bring kids and community members into the halls to enjoy the arts. The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts is a glorious building with something for everyone.

Bing Concert Hall

Bing Concert Hall is located on the campus of Stanford University in California and is home to the Stanford Live performance series. Construction started on this $111.9 million dollar building in 2010, and was finished in January of 2013. The hall holds 842 people all arranged in a “vineyard” format, meaning the seating is arranged in raked tiers, like sloping terraces in a vineyard. This way the farthest seat is only 75 feet from the stage! The architect was Richard Olcott, and the name Bing comes from Peter and Helen Bing, two notable donors, who gave $50 million dollars for the building’s construction. Sharing the same acoustical engineer as the Walt Disney Concert Hall, both halls enjoy similar acoustic flexibility. Because of this, the sound bounces off the walls and ceiling to create a larger and more pure sound for all listening. The exterior is mainly glass with the concert hallâs dome stretching out from the top. Hailed as âthe envy of any big cityâ by The New York Times, the Bing Concert Hall is not one to forget!

Orchestra Hall (Detroit)

Located in Midtown, Detroit, Orchestra Hall is the proud home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Part of what makes this building so remarkable is the fact that it took only four months, from start to finish, to build. In 1919 then Music Director Ossip Gabrilowitsch, agreed to stay in his position only on the condition that a hall would be constructed that was worthy of the orchestra he had built. So, in April of that year, the Detroit Symphony Society purchased the Westminster Presbyterian Church, razed it to the ground, and erected Orchestra Hall in its place. And what a hall it was! A short three years later the Detroit Symphony became the first orchestra ever to broadcast a performance on the radio. By 1934, they had started a tradition of live broadcasts as part of the nationally syndicated Ford Symphony Hour. Unfortunately, Gabrilowitsch died in 1936, and the orchestra was forced to vacate the hall due to the economic stress of the depression. They were on the move until 1956 when they settled in Ford Auditorium, where they stayed for 33 years. By 1970 the Detroit Symphony Orchestra had become one of the most recorded symphonies in America, but they once more needed a new home. The original Orchestra Hall had fallen into almost complete ruin and was headed for the chopping block when local citizens banded together to save the building. They were successful and millions of dollars poured into its restoration. Plaster, paint, and custom elegance was restored to the hall in the hopes of honoring its original design. In 1989 the Detroit Symphony Orchestra moved back into their first home. After additional renovations in 2003, the building became known as the Max M. Fisher Music Center with multiple add-ons to the hall. Today the building stands out with a modern look on the outside and a traditional look on the inside.