Brahms and Schumann

March 14 – 16, 2025

Subscribe to the 24/25 season today! To learn more about subscription packages or to renew your current subscription, visit dallassymphony.org/subscribe. Single tickets will go on sale in late June. To be the first to receive season updates and special offers from the DSO, sign up for our email listing here.

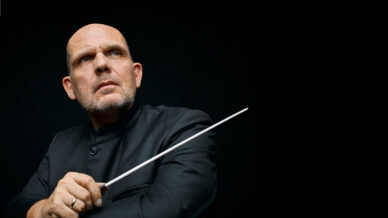

FABIO LUISI conducts

HÉLÈNE GRIMAUD piano

SIPHOKAZI MOLTENO mezzo soprano

JULIA PERRY Stabat Mater

SCHUMANN Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4

Two beloved Romantic works grace this concert program. Acclaimed French pianist Hélène Grimaud solos in Robert Schumann’s masterpiece — a sublime amalgam of rapture and fire, premiered by the composer’s wife Clara who championed it throughout her career. Brahms’s impassioned Fourth is the pinnacle of his symphonic output. The intensity of this autumnal work is illuminated by an inner radiance that will touch your heart with its deep emotions. Siphokazi Molteno “a mezzo with a knockout coloratura” (The Guardian) lends her stunning voice to African-American composer Julia Perry’s Stabat mater, the haunting lament of Jesus’s mother at the cross.